Ballet Costume History

Ballet costumes constitute an essential part of stage design and can be considered as a visual record of a performance. They are often the only survival of a production, representing a living imaginary picture of the scene.

Prima ballerina Anna Pavlova. Early ballerina skirts were heavy, voluminous affairs that severely restricted the dancer's movements. Fortunately, by the early twentieth century, skirts were raised to the knees to showcase pointe work.

Renaissance and Baroque

The origins of ballet lie in the court spectacles of the Renaissance in France and Italy, and evidence of costumes specifically for ballet can be dated to the early fifteenth century. Illustrations from this period show the importance of masks and clothing for spectacles. Splendor at court was strongly reflected in luxuriously designed ballet costumes. Cotton and silk were mixed with flax woven into semitransparent gauze.

From the beginning of the sixteenth century, public theaters were being built in Venice (1637), Rome (1652), Paris (1660), Hamburg

(1678), and other important cities. Ballet spectacles were combined in these venues with processional festivities and masquerades, as stage costumes became highly decorated and made from expensive materials. The basic costume for a male dancer was a tight-fitting, often brocaded cuirass, a short draped skirt and feather-decorated helmets. Female dancers wore opulently embroidered silk tunics in several layers with fringes. Important components of the ballet dress were tightly laced, high-heeled and wedged boots for both dancers, which constituted characteristic footwear for this period.

From 1550, classical Roman dress had a strong influence on costume design: silk skirts were voluminous; positioning of necklines and waistlines and the design of hairstyles were based on the components of everyday dress, although on the stage key details were often exaggerated. Male dancers' dresses were influenced by Roman armor. Typical colors of ballet costumes ranged from dark copper to maroon and purple. A more detailed description of the theatrical dress in the Renaissance and Baroque periods may be found in Lincoln Kirstein's Four Centuries of Ballet (1984, p. 34).

Seventeenth Century

From the seventeenth century onward, silks, satins, and fabrics embroidered with real gold and precious stones increased the level of spectacular decoration associated with ballet costumes. Court dress remained the standard costume for female performers while male dancers' costumes had developed into a kind of uniform embellished with symbolic decoration to denote character or occupation; for example, scissors represented a tailor.

The first Russian ballet performance was staged in 1675, and the Russians adopted European ballet designs. Although costumes for male performers permitted complete freedom of movement, heavy garments and supporting structures for female dancers did not allow graceful gestures. However, male dancers en travesti, often wore knee-long skirts. The luxuriously decorated costumes of this period reflected the glory of the court; details of dresses and silhouettes were exaggerated to be visible and identifiable to spectators viewing from a distance.

Eighteenth Century

From the early eighteenth century, European ballet was centered in the Paris Opéra. Stage costumes were still very similar in outline to the ones in ordinary use at Court, but more elaborate. Around 1720, the panier, a hooped petticoat, appeared, raising skirts a few inches off the ground. During the reign of Louis XVI, court dress, ballet costumes, and fashionable architectural design incorporated decorative rococo prints and ornamental garlands. Flowers, flounces, ribbons, and lace emphasized this opulent feminine style, as soft pastel tones in citron, peach, pink, azure, and pistachio dominated the color range of stage costumes. Female dancers in male roles became popular, and, after the French Revolution in 1789 in particular, male costumes reflected the more conservative and sober Neoclassical style, which dominated the design of everyday fashionable dress. However, massive wigs and headdresses still restricted the mobility of dancers. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Russian ballet and European ballet developed similarly and were often considered an integral part of the opera.

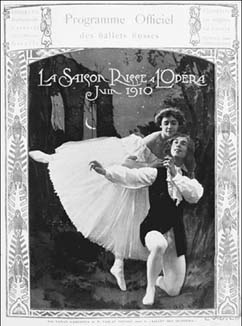

Program featuring Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina. By the end of the nineteenth century, tights were a standard part of the male dancer's ensemble due to the great range of motion they offered.

Nineteenth Century

From the early nineteenth century, the ideals of Romanticism were reflected in female stage costumes through the introduction of close-fitting bodices, floral crowns, corsages, and pearls on fabrics, as well as necklace and bracelets; Neoclassical style still dominated the design of male costumes. Moreover, the role of the ballerina as star dancer became more important and was emphasized with tight-fitting corsets, bejeweled bodices, and opulent headdresses. In 1832, Marie Taglioni's gauze-layered white tutu in La Sylphide set a new trend in ballet costumes, in which silhouettes became tighter, revealing the legs and the permanently toe-shoed feet. From this point on, the silhouette of ballet costumes became more tight fitting. The choreography required that ballerinas to wear pointe shoes all the time. The Russian ballet continued to develop in the nineteenth century and such writers and composers as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Tchaikovsky changed the meaning of ballet through the composition of narrative productions. Choreographers of classical ballet, such as Marius Petipa, created fairy-tale ballets, including The Sleeping Beauty (1890), Swan Lake (1895), and Raymonde (1898), making fantasy costumes very popular.

Twentieth Century

At the turn of the twentieth century, ballet costumes reformed again under the more liberal influence of the Russian choreographer Michel Fokine. Ballerina skirts changed gradually to become knee-length tutus designed to show off the point work and multiple turns, which formed the focus of dance practice. The dancer Isadora Duncan freed ballerinas from corsets and introduced a revolutionary natural silhouette. The Russian impresario and producer Serge Diaghilev marked this era with his creative innovations, and professional costumers like Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst demonstrated, in performances such as Schéhérezade (1910), that the influence of Orientalism had spread from fashion to the stage and vice versa. Indeed, fashion designers like Jean Poiret had already used the tunic shape taken up by dancers in the prewar era, and, in the 1920s, costume designers updated classical Russian story ballets with exotic tunics and veils wrapped around the body. Ballet dancers were dressed in loose tunics, harem pants, and turbans, rather than in the established tutu and feather headdress. Instead of discreet pastel colors vibrant shades, such as yellow, orange, or red, often in wild patterns, gave an unprecedented visual impression of exciting exoticism to the spectator.

Modernism and Postmodernism

Modernism liberalized the rules of ballet costumes, and, after Diaghilev's death in 1929, costume design was no longer impeded by restrictions imposed by traditionalists. Nowadays ballet dancers perform in various costumes, which can still include traditional Diaghilev designs. In postmodern productions like Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, the costume designer Lez Brotherston turned the traditional gracile female cygnets into topless, feather-legged male swans. However, fashion designers of the 1990s have picked up the theme of ballerina shoes. The house of Chanel designed elegant, heelless slippers tied up with ribbons and brought the ballerina shoe from the stage to the street.

The mask in ballet spectacles

Mary Clarke's and Clement Crisp's Design for Ballet (London 1978, p. 34) serves to illustrate a vivid description of the importance of masks in ballet performances to stylize characters: "For demons, this was properly hideous; for nymphs it would be sweetly naïve, rivers wore venerable bearded masks, while dwarfs and juveniles might be encumbered with massive heads. Masks were also sometimes placed upon knees, elbows, and the chest to indicate something more of the character." Half-masks were still worn until the 1770s and were from then on replaced by facial makeup.

Quoted from; http://angelasancartier.net/ballet-costume

BIBLIOGRAPHY

André, Paul. The Great History of Russian Ballet. Bournemouth, U.K.: Parkstone Publishers, 1998.

Chazin-Bennahum, Judith. A Longing for Perfection: Neoclassic Fashion and Ballet. Oxford: Fashion Theory 6, no. 4 (2002): 369 - 386.

Clarke, Mary, and Clement Crisp. Design for Ballet. London: Cassell and Collier, Macmillan Publishers, Ltd., 1978.

Kirstein, Lincoln. Four Centuries of Ballet. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1984.

Morrison, Kirsty. From Russia with Love. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 1998.

Reade, Brian. Ballet Designs and Illustrations 1581 - 1940. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967.

Schouvaloff, Alexander. The Art of Ballet Russes. New Haven, Conn., and London: Yale University Press, 1997.

Williams, Peter. Masterpieces of Ballet Design. Oxford: Phaidon Press, Ltd, 1981.

Wulf, Helena. Ballet Across Borders. Oxford and New York: Berg Publishers, 1998.